How changing our diet can help save the planet

Did you know that about a quarter of all climate change comes from the food we eat? This includes chopping down trees to make land for agriculture, producing and applying fertilisers to the soil to grow food for us and the animals we eat, methane from animal burps and poo, and all the way to the consumer with transport, packaging and refrigeration.

We need to stop burning fossil fuels but, when we do, food will be the biggest contributor to climate change. Looking ahead, the contribution of food to climate change is set to rise, if we are to meet the demands of more people wanting more food.

Different foods contribute very different amounts

What can we do about it? The good news is that different foods contribute very different amounts to climate change, and even for the same food, the amount of impact depends on how it is produced. For example, a large steak and chips dinner causes over 20 times the climate impact of a microwaved potato and beans dinner.

What’s your preferred recipe for spaghetti bolognese? Splitting a 500-gram pack of prime mince between four people, and adding some tinned tomatoes creates a dinner that causes more climate impact than a whole average UK day of food. But simply switching from beef to chicken can reduce the impact by more than three times.

Alternatively, swapping the beef for the same weight of cooked lentils can bring the impact down by more than six times. Some people might find it easier to simply reduce the quantity of beef, perhaps buying better quality meat if possible, and adding in some lentils or more veggies to bulk out the meal and provide extra nutrition.

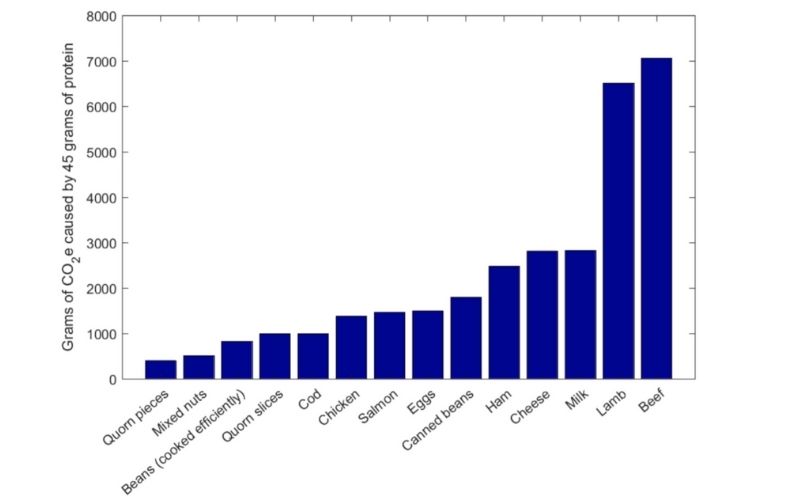

Many people get concerned about protein sources when considering the climate impacts of their food. Red meat, like beef and lamb, top the chart when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions because microbes in their stomachs turn about 5% of their calories into methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Pork products (e.g. ham), chicken and farmed fish (e.g. salmon) contribute to climate change largely because of the food that has to be grown to feed them, which contributes to deforestation. On the other end of the scale, the lowest emissions protein foods include nuts, Quorn and pulses.

Low-emission days

I set myself the challenge of trying to come up with a whole day of food that was reasonably nutritious, yet caused only one-third of the climate impact of the UK average. Staples of the day included bread for breakfast, beans and potato for lunch, and chickpea tikka masala curry for dinner. It’s fine for the climate to include some foods that came by boat, such as long-lasting fruits like oranges or bananas, but avoiding air-freighted goods like out-of-season raspberries or green beans makes a big difference – three portions would have blown my entire climate budget!

But I’m not a chef or a nutritionist, so I really want experts to work together to produce some really delicious and nutritious options for people to choose from. We’ve assembled the latest numbers for the climate impacts from the literature and want people to start getting familiar with the idea that each food has a different climate impact, usually written as ‘gCO2e’ or grams of carbon dioxide equivalent (‘equivalent’ is used because carbon dioxide isn’t the only contributor to climate change, e.g. methane causes about 30 times the climate impact of the same weight of carbon dioxide).

Ultimately though, there isn’t just one number for the climate impact of each type of food, because it depends on how the food is produced. For example, beef from a dairy herd causes about half the climate impact of that from a dedicated beef herd, because the impact is shared out between the beef and the milk. But, how can you know whether you are buying dairy beef? And how can you know whether your fruit came by boat or by plane? And what about all the great work already being done by farmers to reduce soil disturbance and use less fertiliser, which both help reduce climate impacts?

Nutritional labelling has had a big impact on both consumers and food producers, and so on the health of the nation. For example, when the threshold for a red sugar traffic light was changed, food producers quickly reformulated, with the result that no product gained a new red light and the nation consumed less sugar.

I believe that mandatory accredited climate impact labelling would be similarly transformative, and needs to start happening. Would you be interested to see a label on each food packet stating its climate impact?

I appreciate there’s a lot of information already on packets, but even if you’ve never looked at the information, the requirement would incentivise best practice in farming. It would also enable nutrition professionals to give informed answers to citizens concerned about their climate impacts, and propose some fantastic climate-friendly options for us all.

Sarah Bridle is a professor in the Extragalactic astronomy and Cosmology research group in the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics at the University of Manchester. Her book, Food and Climate Change Without the Hot Air is available from most bookshops, £19.99 in paperback and free as an ebook.

Find the right nutritionist for you

All nutrition professionals are verified